Why build a DIY USB barometer when you can buy one?

There comes a moment in many engineering projects where you look at a $10 breakout board, a $15 microcontroller, and a USB cable, and you think: “I can turn this into a USB barometer in an afternoon.” It’s a perfectly reasonable thought. The MS5611 and BMP390 are excellent sensor ICs. Arduino and ESP32 make prototyping fast. The breadboard version works on the first try. Then comes the second thought: “I can fit this into a USB stick form factor. It’ll be perfect.”

This article is for the engineer who has reached that second thought — or who is already midway through building it. Not to talk you out of it, but to lay out the full picture so you can make the decision with all the numbers in front of you.

The prototype is the easy part

Let’s say you’re building a USB barometer around the BMP390, one of Bosch’s latest barometric pressure sensors. You pick up an Adafruit breakout board for about $11. You wire it to an Arduino Nano ($15) or an ESP32 ($8) using I2C — four wires: VCC, GND, SDA, SCL. You install the Adafruit BMP3XX library, upload the example sketch, open the serial monitor, and there it is: atmospheric pressure, temperature, altitude. Working prototype in 45 minutes. Maybe less if you’ve done it before.

If your sensor is an MS5611 on a GY-63 breakout ($6–$12 depending on source), the process is similar. Different library, same I2C wiring, same result. The MS5611 uses a TE Connectivity MEMS die with a 24-bit ΔΣ ADC and factory-calibrated compensation coefficients stored in PROM. The BMP390 uses a Bosch MEMS die with its own compensation model. Both produce excellent raw data.

At this stage, the total bill of materials is under $30 and everything works. This is the moment where the project feels trivially close to done.

It isn’t.

What separates a prototype from a reliable product

The breadboard prototype answers a question: “Can I read atmospheric pressure on my computer?” The answer is yes. But in most professional contexts, the real question is different: “Can I read atmospheric pressure on my computer reliably, repeatedly, and with known accuracy (for weeks or months) without babysitting the hardware?”

That question leads to a very different list of requirements.

Enclosure. The breadboard is not going to survive in a lab, a server room, or a test bench. You need a housing. If you want the USB-stick form factor, you need a custom enclosure, and “custom enclosure” means either a 3D-printed design (which requires a 3D printer, CAD time, and iteration on fit and tolerances) or a commercially available project box that you modify with cutouts. The enclosure must be vented so the barometric sensor is exposed to ambient air, but protected from dust and mechanical impact. If your prototype uses a separate breakout board wired to a microcontroller, you now have two PCBs and a cable to fit inside a housing that also needs a USB connector with strain relief. This step alone can take a full day.

Custom PCB. The alternative to stuffing a breadboard into a box is to design a proper PCB that integrates the sensor IC, the microcontroller, and the USB connector on a single board. This is the clean path, but it involves KiCad or Altium, PCB fabrication lead time (1–3 weeks from JLCPCB or PCBWay), component sourcing, reflow soldering of the MEMS sensor (the BMP390 comes in a 2.0 × 2.0 mm LGA-10 package, not hand-solderable), and at least one revision cycle when the first board doesn’t quite work. For one-off or small-batch production, this path adds weeks and hundreds of dollars.

Firmware robustness. The example sketch works in a demo. For deployment, you need error handling (what happens when the I2C bus hangs?), watchdog timers (what if the microcontroller locks up?), and graceful USB reconnection behavior. If your PC restarts, does the serial port come back cleanly? On Windows, COM port numbering is notoriously unstable: unplug and replug the device and it may appear as a different COM port, breaking your data pipeline. These are solvable problems, but each one consumes engineering hours.

Temperature compensation. Both the MS5611 and BMP390 apply internal temperature compensation, but the quality of the compensation depends on the implementation. The MS5611 datasheet describes a second-order compensation algorithm for temperatures below 20°C and an additional correction below −15°C. Not all Arduino libraries implement the full algorithm. If your application spans a wide temperature range, you may need to verify (or rewrite!) the compensation code. The BMP390 handles compensation internally in its ASIC, which is more convenient but also means you cannot inspect or correct the algorithm.

Calibration and traceability. Your DIY barometer’s accuracy depends on the factory calibration of the sensor IC, your PCB layout (trace routing near the sensor can introduce thermal gradients), and the quality of the power supply (noise on VCC affects ADC readings). Out of the box, an MS5611 breakout board delivers ±1.5 mbar accuracy under ideal conditions. But you have no certificate to prove it. For many engineering and laboratory applications, “it reads about 101.3 kPa” is not sufficient. You need an accuracy statement backed by a traceable calibration. If your client, your quality system, or your regulatory framework requires ISO 17025 traceability, your DIY barometer cannot provide it.

Long-term reliability. Exposed header pins corrode. Breadboard connections develop intermittent contact failures. USB-serial adapters (especially cheap CH340-based clones) have been known to drop data under sustained logging. The BMP390 breakout board from Adafruit is well made, but it was designed for prototyping, not for permanent installation in an environment where it will run unattended for months. That is not a flaw in the product: it’s a difference in intended use.

The real cost of a DIY USB barometer

Here is an honest accounting of what it costs to turn a working breadboard prototype into a deployable USB barometer. The engineering hours assume a competent engineer who has done this kind of work before.

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

| BMP390 or MS5611 breakout board | $6 – $12 |

| Microcontroller (Arduino Nano, ESP32, etc.) | $8 – $20 |

| USB cable, connectors, passive components | $3 – $5 |

| Enclosure (3D-printed or project box) | $5 – $15 |

| Custom PCB (optional, per unit for small batch) | $15 – $50 |

| Subtotal: hardware | $37 – $102 |

| Firmware development and debugging | 4 – 12 hours |

| Enclosure design and iteration | 2 – 6 hours |

| Testing and validation | 2 – 4 hours |

| Serial port integration code (Python, LabVIEW, etc.) | 2 – 6 hours |

| Subtotal: engineering time | 10 – 28 hours |

If your engineering time costs $50/hour (conservative for a professional engineer), the labor component alone is $500 to $1,400. The total cost of the DIY barometer is therefore not $25; it is $537 to $1 502, depending on how many problems you encounter and how polished the result needs to be.

And this calculation does not include the cost of ongoing maintenance: firmware updates when the Arduino toolchain changes, replacement of components that fail, or the time spent diagnosing why the readings drifted after six months of continuous operation.

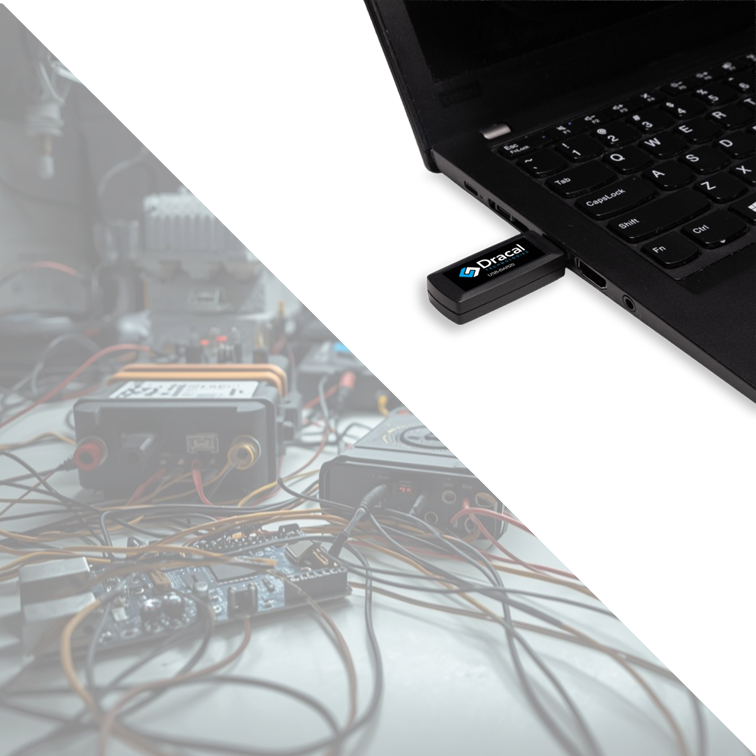

What you get for $158

The Dracal BAR20 uses the same MS5611 sensor IC found on most popular breakout boards. It integrates the sensor, a 24-bit ΔΣ ADC, temperature compensation (including the full second-order algorithm), USB communication, and a robust enclosure into a 62 × 20 × 10 mm USB key. Every unit is individually factory calibrated, and ISO 17025 traceability certificates are available on request.

On the software side, the BAR20 ships with free tools that eliminate the serial-parsing problem entirely. The command-line tool (dracal-usb-get) returns the measurement as a plain number. The REST JSON API exposes sensor data over HTTP for web or application integration. DracalView provides graphing, logging, and unit conversion with a graphical interface. Code examples are available in Python, C, C++, C#, Java, Node.js, LabVIEW, and more. These tools work on Windows, macOS, and Linux.

The BAR20-CAL variant adds a 3-point user calibration mechanism, where calibration offsets are stored directly on the device, not on your PC. This means you can move the instrument between computers without losing your calibration.

In other words, the $158 includes the sensor, the electronics, the enclosure, the firmware, the software, the calibration, and the support. The hours you would have spent building, debugging, and maintaining a DIY solution can be spent on whatever the barometer was actually meant to serve.

When building it yourself still makes sense

There are legitimate reasons to go the DIY route, and this article would be incomplete without acknowledging them.

Learning. If the goal is to understand how MEMS barometric sensors work, how I2C and SPI protocols behave, or how temperature compensation algorithms are implemented, building a barometer from a breakout board is an excellent exercise. The MS5611 datasheet (TE Connectivity AN520) is a masterclass in sensor compensation mathematics. The educational value is real, and it cannot be replaced by buying a finished product.

Non-standard form factors. If your barometer must fit inside a specific enclosure that no commercial product can accommodate — say, a narrow tube, a custom drone frame, or a sealed chamber with a feedthrough — then a custom PCB built around the bare sensor IC is the right approach.

Extreme volume. If you need 10,000 units of a barometer integrated into a product you manufacture, designing a custom board around the BMP390 or MS5611 will bring the per-unit cost well below $158. At that scale, the engineering cost is amortized over the production run and the math changes fundamentally. (That said, Dracal also offers OEM integration options for volume applications.)

Specifications that don’t exist commercially. If you need a barometric sensor with a specific sampling rate, a specific ADC resolution, or a specific physical configuration that no commercial product provides, you have no choice but to build it.

For everyone else, i.e. the engineer who needs a reliable, calibrated atmospheric pressure reading on a PC for a lab, a test system, or a monitoring application, the buy-vs.-build analysis tilts heavily toward buying.

And if I also need temperature and humidity?

The BAR20 measures atmospheric pressure only. If your project requires temperature and relative humidity alongside pressure, the Dracal PTH450 combines all three parameters in the same USB form factor, with the same CLI, the same API, and the same free software. For the engineer who was about to build a multi-sensor USB device around a BME280 or a BMP390 + SHT35 combination, the PTH450 eliminates the entire integration challenge.

About Dracal's BAR20 and other sensors

The Dracal BAR20 is a ready-to-use USB barometer that provides a simple alternative to building a custom atmospheric pressure sensor with a microcontroller and serial breakout board. It is compatible with Windows, macOS, and Linux, and integrates with any software environment thanks to its CLI interface, virtual COM port, or JSON REST API.

Always offered at no extra charge with our products!

EASY TO USE IN YOUR OWN SYSTEM

- Ready-to-use, accurate and robust real-time data flow

- Choose the interface that works best for you (CLI, virtual COM, REST API)

- Code samples available in 10+ programming languages (Python, C/C++, C#, Java, Node, .Net, etc.)

- Operates under Windows, Mac OS X and Linux

- Usable with LabView (CLI guide, Virtual COM guide)

- All tools packaged within one simple, free of charge, DracalView download

FREE DATA VISUALIZATION, LOGGING AND CALIBRATION SOFTWARE

- Get up-and-running in less than 3 minutes

- Operates under Windows, Mac OS X and Linux

- Real-time on-screen graphing and logging

- Log interval down to 0.5 second and configurable units (°C, °F, K…)

- Simultaneous use of unlimited Dracal sensors supported

- Simple user-calibration (products with the -CAL option)

- Connectivity with SensGate Wi-Fi/Ethernet gateway

PRODUCTS YOU CAN TRUST

Approved by engineers, scientists and researchers around the world.

Thousands of companies trust our products worldwide:

Not sure if your project will benefit from Dracal’s solution?

Contact us, tell us about your project, and we’ll quickly determine if there’s a fit.

"*" indicates required fields